Truths about Whisky.

Long before this book was published in 1878, the disruptive technology of the Patent, Coffey or Column Still was wreaking havoc in the Irish whiskey industry.

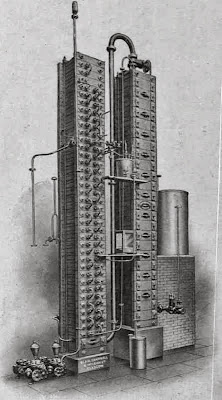

Patented by Aeneas Coffey in 1831, this still could produce almost pure alcohol faster and more cheaply than the huge copper pot stills mainly used before this invention. Coffey himself had seen the Stein Column Still, possibly the first commercially successful column still, built by Clackmannanshire distiller Robert Stein, a member of the Stein distilling family. The Stein still had three preheaters and steam boiled in a separate vessel was used to heat the wash, which was intermittently sprayed by pistons into a series of chambers. The chambers were divided by crude cloths (probably haircloths). The cloth permeated ethanol well, but less so water and soluble matter, therefore acting both as a rectifier and a filter. It enabled large amounts of distillate to be produced in a single run and improved the heat economy compared to the pot stills. The process had to be stopped to allow discarding the excess oily residue, so it was not exactly continuous operation. The Coffey Still replaced the haircloth rectifier with copper plates, which proved to be more efficient and needed less maintenance.

Coffey still

Since the Coffey still distillation product was almost colourless and tasteless, (and so was referenced as 'silent spirit' in the book) the alcohol barely resembled traditional malt whiskey, but it could be "blended" with traditionally made whiskey to create a cheaper, lighter tasting drink that immediately found favour with the consumer.

The great Irish distilling houses railed against this innovation, refusing to accept that the resulting product was worthy of being called whiskey, and they spent decades trying to get the law changed to their way of thinking. In this, as we know, they failed, as most Irish whiskey sold today is just such a blend.

In 1878, however, the fight against the Coffey still product was still ongoing. The four great Dublin whiskey houses - John Jameson, William Jameson, (both founded by the Jameson family, originally from Alloa, Clackmannanshire) George Roe and John Power - had joined forces to campaign for a strict legal definition of whiskey. They found that the London parliament were unreceptive, and so they decided to appeal to the consumer directly. The result was this book, Truths About Whisky.

The book outlines their disdain for the supposedly inferior Coffey Still product, and also bemoans some of the sharp practice of their competitors.

It's not surprising that, in the midst of all of the fraud and fakery, the Dublin distillers failed to spot the potential of the Coffey still, if used legitimately. We now accept that grain spirit does have a milder character and can acquire further personality during maturation. Irish blended whiskeys today are among the top tier of such products.

Truths About Whisky, in contrast, is adamant that grain whiskey is merely "Pure alcohol and water, or nearly so, without distinctive flavour or quality, and without capacity for improvement."

The grievances listed in Truths About Whisky were not finally settled, one way or the other, until the Royal Commission on Whisky report in 1909.

It is the perceived superiority of malt whisky that the book below tries to convey.

Truths about Whisky

Dublin 1878

CHAPTER I. - THE POSITION OF THE AUTHORS.

The four firms of Whisky distillers by whom this book is published, Messrs. John Jameson and Son, Wm. Jameson and Co., John Power and Son, and George Roe and Co., who have for the last two years been engaged in an endeavour to place some check upon the practices of the fraudulent traders by whom silent spirit, variously disguised and flavoured, is sold under the name of Whisky, have come to the conclusion that their efforts in this direction are more likely to be successful if their own position with regard to the genuine manufacture is exactly known.

Within the limits of the spirit trade, of course, this condition is already fulfilled; but it is important that it should also be fulfilled with regard to consumers and to the public. The fraudulent trade, although it could not exist without the complicity of great houses, yet exists mainly by the sufferance of the retail purchaser; for, if he were to insist upon being supplied with Whisky when he asks for it, and with silent spirit only when he asks for that, there would be an end of the element of deception which now enters so largely into the case. The authors cannot raise the smallest objection to the manufacture and sale of silent spirit, in whatever quantities it may be required for the supply of any legitimate demand; either as an avowed substitute for Whisky for the use of those who like it, or for any one of an infinite number of possible applications in the arts.

The point of their objection rests solely upon the substitution of silent spirit for Whisky when Whisky is demanded; and the validity of this objection must be admitted to depend upon the correctness of their definition of Whisky as a spirit which is distilled either from malt, or a mixture of malt and un-malted corn, from barley or oats, or malt, or from a mixture of them, in a so-called pot-still, which brings over, together with the spirit, a variety of flavouring and other ingredients from the grain. It is obvious that, if the grain were mouldy, or damaged, or for any reason ill-flavoured, the spirit thus made would be undrinkable; or, at least, would be of manifestly inferior quality; and hence the method of manufacture described requires, as an essential condition of its success, that only the very best grain and malt which can be procured should be employed.

Silent spirit, on the contrary, is made in what are called "patent" stills from any vegetable matter which contains the materials necessary for fermentation; and the patent still, when it is properly and carefully managed, brings over alcohol and water only, leaving all flavouring matter behind. Hence, damaged grain or potatoes, molasses refuse, and various other waste products, are cast into the all-devouring maw of the patent still, and they all yield alcohol and water by distillation; so that, if alcohol and water were Whisky, they would all yield Whisky. As a matter of fact, these things no more yield Whisky than they yield wine or beer. Alcohol and water enter into the composition of all fermented drinks without exception; and these drinks are indebted for their severally distinctive qualities to the other things, over and above alcohol and water, which they respectively contain. In the case of Whisky, the distinctive characters are due to the grain products already mentioned; and these are not only sources of flavour, but also, when sufficiently matured by keeping, undergo development into a number of volatile ethers, so subtle that they almost elude chemical analysis, but which are easily discoverable by the nose and by the palate, and still more certainly by their power to produce exhilaration, which is altogether independent of the alcohol which holds them in solution. Fine Whisky, of good age, is so fragrant from the presence of these ethers that it might almost be used as a perfume; while silent spirit undergoes no change by keeping, and has only a peculiar penetrating odour of a kind which cannot be mistaken when it has once been perceived.

In order to make silent spirit into a colourable imitation of Whisky-for it could not pass muster alone-it is drugged with different flavours, to which further reference will be made in the sequel.

Having said thus much by way of prelude to the general argument of the book, we come now to details about the position of the authors-details which are given for the sake of showing to what extent they are entitled to speak with authority upon the particular matter in hand.

With regard to the first of the firms in question, that of John Jameson and Son, its origin cannot now be traced. There is a tradition that it was founded by three gentlemen, one of whom was a baronet and another a retired general, but that they were unsuccessful in their enterprise and lost their capital. There is no one living who knows, and there is no discoverable documentary evidence to show, what was the date of foundation, neither can we even say at what date, prior to 1802, the distillery passed into the hands of the ancestor of the present proprietors. We only know that it has been in the possession of the same family for several generations, and that it has long been conspicuous, primus inter pares, for the unchallenged excellence of its products.

The second distillery, that of Messrs. Wm. Jameson and Co., has been in the possession of the family of the present proprietors since the year 1779. When purchased by their ancestor it was only a small undertaking; but from the superior quality of the Whisky which it produced, considerable enlargements soon became necessary. These enlargements were repeated from time to time; and, about eight years ago, the increasing demand for the Whisky rendered it necessary to increase the plant to the extent represented by an outlay of nearly £100,000. The yards and buildings now occupy a surface of ten acres of ground; and comprise corn stores, kilns, grinding mills, mash-house, spirit stores, cooperage, bonded warehouses, fermenting lofts, and other requirements for the conduct of the manufacture. The corn stores are capable of containing 30,000 barrels of sixteen stone each. The grinding mills can turn out 150 tons of ground corn in twenty four hours. The mash-house, or brew-house, contains two tuns, which are the largest in the kingdom, being upwards of forty feet in diameter and ten feet deep, besides brewing vats and boiling coppers. In the fermenting lofts there are thirteen fermenting vessels or backs, some of which will contain 100,000 imperial gallons. The still-house is in proportion to the other arrangements, and contains four large pot-stills. In the spirit-house, the vat from which the Whisky is racked into casks keeps twenty men employed at a time. The bonded warehouses are nine in number will contain 20,000 hogsheads, and have been carefully constructed with a view to proper ventilation, and to the preservation of the spirit under circumstances favourable to its being matured. The present cooperage was only completed about five years ago, end covers an acre of ground, where there is every modern appliance for cleansing and purifying casks. The water supply, of which there will be more to say hereafter, is mainly derived from the river Poddle, which flows through the distillery.

The firm of John Power and Son, John's Lane Distillery, Dublin, was established in 1791, by Mr. James Power, the great-grandfather of the present proprietors, and during the last few years the whole distillery has been rebuilt upon an improved plan, and fitted with new plant. The works now cover five acres of ground, and contain appliances similar to those of the distillery last described. The storehouse for raw or un-malted corn is 153 ft. in length by 95 ft. in breadth. It is five stories high, and is capable of containing 3,000 tons of grain. The grain is delivered in two receiving rooms on the ground floor, from whence it is conveyed to the lofts by elevators, and is then distributed by archimedean screws. The mill contains four pairs of stones, driven by a steam. engine of one hundred and sixty nominal horse power, and is capable of grinding upwards of sixty tons every twenty-four hours. The barley for malting is received into separate lofts, where it is distributed for the subsequent processes in the same manner as the raw barley; and the meal is conveyed by elevators to over the brewhouse, whence it is discharged into large mash tuns beneath, each of which is sufficiently capacious to mash thirty-five tons daily.

The still-house contains four pot-stills of large capacity, together with five receivers and three chargers. The Whisky produced by these stills is pumped from the testing room to the spirit store, where it is put into large vats, and reduced to an uniform strength of twenty-five per cent. overproof before it is filled into casks. The bonded warehouses are seventeen in number, and afford storage room for two years' manufacture.

The fourth, or Thomas Street Distillery, that of George Roe and Co., was founded before the middle of the eighteenth century, and became the property of an ancestor of the present proprietor, Mr. Henry Roe, junior, in the year 1775. Originally of small dimensions, the works have been extended in various times during the last eighty years, and within the last ten years very large sums of money have been expended upon them. Four additional stills were built in 1872; and these, with other plant erected shortly afterwards, have almost doubled the producing power of the concern, which is now the largest pot-still distillery in the United Kingdom. During the course of 1877, large corn stores and a new drying kiln were added; and with this increased power about 5000 barrels of barley and oats are dried every week. The corn-mill contains seven pairs of stones, and can grind 1500 barrels of corn in twenty-four hours. There are three mash tuns, the largest of which is 36 ft. in diameter and 7 ft. 6 in. in depth, and eight large pot-stills of the usual construction.

For very many years before steam power was introduced, the machinery of this distillery was driven by wind; and the windmill employed for the purpose, which is upwards of 120 ft. in height, still remains, and is surmounted by a copper dome, on which stands a large iron figure of St. Patrick. The windmill has, however, been superseded by steam engines, the three largest of which work up to 120, 150, and 180 horsepower respectively. Besides these, there are several smaller engines, used for driving pumps and for other minor work. The chargers, receivers, worm-tubs, and other necessary utensils, are all on a scale of magnitude corresponding with the rest of the plant; and the Whisky is stored in warehouses, of which there are seventeen, several of them capable of containing 12,000 casks each. Plans for large additions are at present under consideration, and a great extension of the works cannot be long delayed.

It will be observed, in the foregoing enumeration of some of the chief points of the four distilleries, that no mention has been made of patent stills; and the four establishments are all alike in this respect, that no patent still exists among them. They make, and they can make, nothing but pot-still spirit; that is to say, real genuine Whisky, and they have no means, appliances, or opportunity, for mixing this with any inferior liquid before it is sent out to their respective customers.

Besides those of the Authors, there are perhaps, fourteen other distilleries in various parts of Ireland, in which nothing but pot-still Whisky is made. Those situated in the provinces are mostly on a small scale, and it may fairly be said that they bear to the great Dublin firms the sort of relation which is borne in England by the ale and beer brewers of small market towns to the Breweries of London or of Burton-upon-Trent. The provincial pot-still Whisky is a genuine article, fairly entitled to be called Whisky; but the Dublin houses, by their long-established position and their large capital, not only command the grain market, and can secure for themselves the pick of each years' harvest, but they also command the best manufacturing skill which money and experience can procure.

While such, for many years, has been the Authors' position of supremacy as manufacturers, the conditions of the Whisky Trade have nevertheless been such as to keep their names, to a very great extent, concealed from the knowledge of consumers. It has been the practice of the four firms for many years, not merely to sell chiefly to large dealers, but to sell without taking precautions for the preservation of the purity and simplicity of their products; and out of this practice sundry complications ultimately arose. Certain of these dealers began to push their own trade with public-houses and private consumers by means of costly and continued advertisements; and in this way the position in the estimation of the public which should have been held by the best manufacturers was gradually usurped by the dealers; while, in course of time, some of the dealers, finding that they had established a market for their own wares, began to seek how they might turn this market to the largest pecuniary account, by increasing their profits upon the Whisky. They were not content with the honest profit which they derived as middlemen, but sought to increase this profit even at the cost of having recourse to means which rendered it no longer honest.

The first step in this direction was to adulterate the Whisky of the Dublin makers with provincial Whisky of a cheaper and coarser character, and to sell the whole mixture at the price of the more costly of the two varieties of spirit which entered into its composition. At first, this was done somewhat bashfully, and under the pretext that these dealers, by dint of great knowledge and experience, had found out how to mix two or more varieties of Whisky in such manner as to produce a result better than any of its component parts. The process was delicately called "blending" and, although it would seem that nothing more than a faint gleam of common sense was required in order to show the character of the proceeding, it is said that there are people still living who seriously believe that to mix good and bad Whisky together is a desirable proceeding in the interests of the consumer. The first "blenders" were enabled, to some small extent, to undersell those of their rivals who had not yet discovered or practised the art; but in trade such practices soon become known to those whose business it is to find them out, and blending became almost universal. In the meanwhile, the increasing employment of the patent still had brought copious supplies of silent spirit into the market; and the blenders soon availed themselves of these supplies as sources of additional cheapness. They were no longer content to dilute the genuine Dublin with the coarse provincial Whisky; but they afterwards diluted the mixture with silent spirit, and they selected the coarsest and strongest tasted provincial Whisky they could find, in order to give flavour to the otherwise insipid compound.

By-and-bye, the Dublin Whisky was first diminished in quantity, and ultimately was even suffered to drop out altogether, and in course of time the provincial Whisky followed the Dublin. Pressure was next brought to bear upon the revenue authorities to permit the "Blending" of "Plain British Spirit" in bond; and dealers were allowed to bring silent spirit from any part of the United Kingdom to any other part, and to mix it with any other spirit, being of British manufacture, in any proportions which seemed good to them. Great manufactories of silent spirit existed in Scotland; but Irish Whisky was held in more general esteem than Scotch, and so the Scotch and English silent spirit was sent to Dublin, to be returned from thence to England as Dublin or Irish Whisky. Thousands of gallons of silent spirit were sent from Glasgow or from Liverpool to Dublin or to Belfast; and, having been mixed in bond with other spirit like itself, from the same or from other sources, and perhaps with a little, say 10 per cent., of genuine coarse Whisky, the compound was reshipped immediately from the Irish port, with a Belfast or a Dublin Custom-House permit, as Dublin or Irish Whisky, was sold under this name in England, and was sent from England to all other parts of the world. The active competition among dealers to undersell one another drove them continually to lower and lower shifts, until at length even the modicum of coarse Whisky was omitted from the mixture, and an attempt was made to give an approach to the flavour of Whisky by chemical means alone. The great Dublin houses were in time brought face to face with a very serious state of things.

The manufacture which their firms had introduced, and which had become famous, was being gradually superseded by a fraudulent admixture of less than half the value, which was retailed at a lower price than that at which genuine Whisky could be sold to the wholesale dealer, or even produced at the distillery. The imitation was so wanting in all the essentials of real Whisky that it had no other value than as a mere stimulant for dram-drinkers, possessing none of the dietetic qualities of genuine Whisky; and the consumer, who had no means of getting Whisky at all, would soon have ceased to know even what it ought to be, so that the genuine spirit would have been displaced and driven out of the field by the fictitious. The make of the great firms seldom reached the public in its purity, but only as a flavouring ingredient in some few of the best of the spurious kinds; and even in these the importance and meaning of this flavour were gradually ceasing to be recognised. Some of the dealers, who had at first been content to import their silent spirit from England or Scotland, at last began to find that they could make it themselves; and a vastly increased number of patent stills invaded even the soil of Ireland. In Belfast, Cork, Dundalk, Limerick, and Londonderry patent stills were established, sometimes with, and sometimes without, pot-stills in the same distillery; and silent spirit, always under the name of Whisky, became an extensive Irish manufacture. In these circumstances the authors had only two courses open to them. It is much more costly to produce Whisky than to produce silent spirit; and, as long as both were supposed to be essentially the same liquid, and were in competition with one another, the silent spirit lowered the price of Whisky until the latter could scarcely be sold at a price to pay for its manufacture.

The Dublin firms might have thrown down their pot-stills, replaced them by patent ones, and have gone into the silent spirit or fictitious Whisky trade with an amount of capital, and with other advantages, which would have enabled them to defy the competition of smaller and newer establishments. Instead of doing this, they determined to accept the only possible alternative, and to appeal to the public in defence of the purity and excellence of their manufacture. They determined to come out from behind the veil of middlemen by which they had too long been concealed from the consumer, and to declare the true nature of the stuff which was being sold as Whisky and of the imposition which was being practised upon the public. They do not in the least degree desire to interfere with the manufacture of silent spirit; but they do wish to interfere with its being sold under the name of Whisky. They had scarcely arrived at the determination to take some joint action in the matter, when the Times paper devoted an article to the subject, in which the fraudulent character of the so-called Whisky trade was briefly, but forcibly, described, in terms the precise accuracy of which has not been, and cannot be, impugned. Other newspapers, notably the Daily Telegraph, Punch, and the Medical Examiner, followed the lead of the Times upon the question; and the authors of this volume, as their first step in the campaign upon which they had determined to enter, caused copies of the newspaper articles, with a connecting thread of narrative, to be printed in pamphlet form and widely circulated. The effect of this publication soon became apparent. Consumers began to learn what Whisky was, and what it ought to be; and to distinguish it from silent spirit, however cunningly flavoured. The public began to take the matter into their own hands, and to insist upon being supplied with what they asked for. The true nature of blending was rendered manifest to the humblest capacity; and the practice was reduced from the level of a fine art to that of a vulgar fraud. Members of the House of Commons began to take interest in the question; and some awkward inquiries were made of Ministers with regard to the facilities for fraud which were afforded by the Customs Regulations.

There was abundant evidence that the Authors had not over-estimated either the strength of their position or the righteousness of their cause; and they have been encouraged to persist in their endeavour to spread abroad a knowledge of the nature of Whisky and of its counterfeits, as well as of the conditions under which the trade in counterfeit Whisky has arisen and has been carried on. In such an endeavour, it is an essential condition of success to act upon the well-known principle of the late President Lincoln, and to keep on "pegging away." The first pamphlet has done its work; and these pages, which contain a more general and more extended view of the whole subject, have been written in order to replace it.

CHAPTER II. - THE QUALITIES AND POPULARITY OF GENUINE DUBLIN WHISKY.

Dr. Johnson defines Whisky to be a corruption of Usquebaugh, an Irish and Erse word, which signifies the water of life. He adds that the Irish sort is particularly distinguished for its pleasant and mild flavour, but that the Highland sort is somewhat hotter; and he explains this in a way which, if it was ever correct, has long ceased to be so. He says that the Irish sort is drawn, i.e., distilled, from aromatics; meaning, we presume, that aromatic substances were added to the mash of grain, in order to give a pleasant flavour to the result. He therefore bears testimony to the correctness of our argument, that genuine Whisky derives a flavour from the substances from which it is distilled, and it is plain that patent still or silent spirit, which is not thus flavoured, cannot fulfil the terms of the definition, and is not Whisky. In Dr. Johnson's time, however, and for long after, the manufacture of Irish Whisky was carried on in a very primitive fashion, and the bulk of the spirit was drunk when quite new, partly from want of knowledge of the good effects of keeping it, partly from want of storage conveniences, and sometimes to conceal the precious brew from the prying eyes of the Collectors of Revenue.

We are merely hazarding a conjecture, but it seems more than probable that the first "Old" Irish Whisky became so from being buried in haste for the purpose of concealment, and perhaps not disinterred until after the lapse of years. Unless in such circumstances as these, we fancy Whisky would always have kept badly among our countrymen, who, like the Scotchman lately made famous in Punch, would not be likely to sleep well when there was any quantity of the precious liquid in the house. However this may be, and whether or not we do our countrymen an unintentional injustice in the supposition, there is evidence that the manufacture more than a century ago had become established in Dublin, and in the hands of the ancestors of the Authors; who, there can be no doubt, would soon discover that the addition of the aromatics was unnecessary, if the spirit could be kept long enough to acquire the peculiar and inimitable fragrance which is given to it by age, and by age alone. In order fully to explain this fragrance, it would be needful to enter into chemical details of a kind which would have little interest for readers who are not already conversant with them; but the general facts may be briefly expressed.

The pot-still, as already stated, does not yield a product containing merely alcohol and water, but one which also contains, in intimate mixture, or in solution, many other matters which are yielded by the grain, either as educts, matters which naturally exist and are simply taken out, or as products, matters which are themselves the results of chemical changes in the grain elements during the process of fermentation and distillation. These substances are present in new pot-still Whisky, chiefly in the form of volatile oils and vegetable acids, and their quantity, as well as their precise characters, will depend greatly upon the quality of the grain, upon the way in which it has been treated prior to distillation, and upon the skill and care with which the distillation has been conducted. Between wine and Whisky there is a close parallelism; for in both the new liquid is comparatively unpleasant, and in both it contains materials which shape themselves, if the opportunity is afforded them, into fresh compounds which are highly and deservedly esteemed. These materials are, as said above, chiefly vegetable acids and volatile oils; and the mutual reactions which occur between them and the alcohol, lead to the gradual formation of various ethers of great fragrance. It is well known that alcohol, when but little diluted, restrains organic change; and hence, as a general rule, the greater the alcoholic strength of any liquid, the more slowly will it undergo the changes which constitute maturation.

A pure wine of high class, say a fine vintage Burgundy, undergoes maturation comparatively speedily; and, after having been only three or four years in bottle, it fills the room with perfume as soon as the cork is drawn. Wine of equally good original quality, when brandied for the English market or to protect it during a voyage, will undergo maturation more slowly and better when in greater bulk; whence the long time required to bring some samples of Port to perfection, and whence, also, the love of connoisseurs for magnums. The finest Dublin Whisky, when made, is reduced to a uniform strength of twenty-five per cent. overproof; and is stored in casks of considerable size. Its great alcoholic strength causes it to undergo change only tardily; so that its full maturity and highest excellence cannot be reckoned upon under an age of from three to five years in the wood.

The grain constituents of perfectly new Whisky are not palatable in the estimation of people in general; but after about a year the Whisky may be said to be drinkable, after about two years to be good, and after about three years to be as good as anything with which the average consumer is likely to become acquainted. Those, however, who have only drunk three year-old Whisky, can scarcely form an idea of the effect of longer keeping, always in the wood. The spirit is too strong, the preservative effect of its alcohol is too decided, for any beneficial change to occur in a small bulk hermetically sealed in a bottle, and maturation only becomes complete in large bulk and in wood, which permits the loss by evaporation of much of the original spirit. In order to arrive at perfection, it may be laid down as a general rule that Whisky stored at twenty-five per cent. over-proof should be left in the cask until its strength has fallen considerably; it may then be bottled, and preserved for an indefinite time without further change. When a bottle of such Whisky is opened, it literally, like fine old Burgundy, fills the room with its fragrance, and that fragrance is more delicate than anyone who is unacquainted with it, or who is acquainted only with the smell of common so-called Whisky, could by any possibility conceive. The fragrance is an evidence that all the grain products additional to the alcohol have undergone decomposition, and that their elements have been re-arranged into fresh combinations of a kind analogous to the vinous ethers, and which, like these, are among the most exhilarating of all stimulants. The stimulating characters of new wine, or of new Whisky, are due only to the quantity of alcohol which each contains, and may, therefore, be ascertained by the balance and the test-tube. But the stimulating characters of old wine or of old Whisky are due also, and probably, in much larger measure, to these ethers, which, like nearly all the bodies of their class, are known to sustain the action of the heart and pleasantly to excite the mental faculties, without producing the subsequent depression which so often attends upon the use of alcohol alone.

Unlike the alcohol, the ethers are not measurable. They are extremely volatile, as is fully shown by the prompt diffusion of their perfume; and they are also, in chemical language, so unstable that they can neither be fixed nor analysed. They all consist of the same elements, and so far, when examined by ultimate analysis, or resolution into their ultimate component parts, they are all pretty nearly alike. Their different properties depend upon minute differences in the proportions of these ultimate elements, or even in the molecular arrangement by which they are combined, and these differences defy analysis, although the results of each arrangement may produce a different impression upon the human senses, and a different effect upon the human frame. Chemically speaking, a stench and a perfume, a poison and a remedy, are often separated from each other by curiously fine distinctions, or by differences of which we should never conjecture the importance, if this importance was not constantly made manifest to us by difference of effect. The ethers of which we have spoken all belong to what may be called the fusel-oil family; and, in some varieties of spirit, fusel-oil is among the forms in which they first appear.

A Whisky containing an excess of fusel-oil is said to produce a peculiarly violent and dangerous form of inebriation, and such an excess is only produced either by badly-conducted distillation or by the use of improper materials.

These ethers, or certainly the common and at first unpalatable grain products, may be likened to those qualities in youth which sometimes, especially if not wisely guided, display themselves by the process known as "sowing wild oats," but which, when a certain amount of irregular or untrained energy has been expended, form the basis of some of the noblest and most useful characters. Without the grain products the spirit would be alcohol and water, and nothing more, with no power of development and no capacity for improvement. With them, always supposing that they are yielded by good and well-managed grain, the capacities of improvement are infinite; and the Whisky, which when new is unpalatable, may yet, when it is old, more than maintain the best traditions of the family from which it springs.

In the days of our forefathers, when it was customary to drink solemnly to what were then called "sentiments," one of the most popular of these was the expression of a hope that the evening's pleasure might bear the morning's reflection. It is, perhaps, one of the most striking qualities of genuine and mature Dublin Whisky that it will bear this crucial test. The carefully-brewed glass of toddy, which enlivens talk and quickens fancy when friends are met together round the fireside, leaves no manner of sting behind. It conduces to quiet and dreamless slumber, and it allows the sleeper to wake refreshed, with a cool palate and an easy head, fit for the duties or the pleasures of the coming day. We once met at a dinner-party a wine merchant of great experience, whose opinion was asked about one of the vintages which graced the board. He replied, "I will tell you all I think about it in the morning." We believe that, especially for the unskilled in spirits, there is no better test than this.

Connoisseurs will tell, with a near approach to certainty, the qualities of a real or pretended Whisky by taste and odour, and especially by taste and odour after dilution with cold water; but for those who are not connoisseurs the best test is the state of the head and of the mouth next morning, when the spirit in question has been taken over night. We mean, of course, when it has been taken in moderation, for alcoholic excess, however good the alcohol, is always and to everyone injurious; if not at once, at least ultimately. We claim, however, for genuine Whisky, that it is the most wholesome form in which alcohol can be consumed, and that the ethers which it contains materially assist the alcohol in its beneficial action upon the organism. Unlike some wines, Whisky has no tendency to produce acid indigestion, and it is therefore especially suited to those who inherit, or who have developed for themselves, a gouty constitution. The experience of sportsmen proves it to be the best stimulant during long periods of exertion, when exposed to wet and cold in pedestrian excursions, in deer-stalking, shooting, fishing, or other forms of sport. As applied to these uses, there can be no doubt that the grain ethers play a most important part, acting, to a great extent, as better substitutes for alcohol, and rendering a smaller dose efficacious for the purposes required. We are committed, as a matter of course, to an entire dissent from the doctrines of those fanatical teetotalers who hold that alcohol, in whatever quantity, is always and everywhere injurious, and we cannot be expected to engage in any argument with them; but we must, nevertheless, express our surprise, assuming that they desire to make converts among reasonable and reasoning men, that they should have so completely left out of account, in the various experiments which some of their body profess to have conducted, the way in which the action of alcohol may be modified by the various substances with which it may be combined.

We read, for example, of experiments made with “brandy;" but what is brandy? If the experiments had been made with something which was called Whisky, it would have been highly important to discover whether the liquid used was really Whisky containing ethers in solution, or silent spirit consisting only of alcohol and water. We must remember that the ethers of wine are so potent that, if separated and inhaled, they soon produce a complete insensibility, during the continuance of which a surgical operation may be performed without the knowledge of the person who has inhaled them. Surely it is absurd to suppose that an agent so powerful as this can exert no influence when it is swallowed, or that it can be left wholly out of account in estimating the qualities of any liquid which contains it. We maintain that the presence of the grain ethers is the rationale of the peculiar qualities of fine Whisky, which is indebted to these ethers for a power of stimulation far in excess of its alcoholic strength, as well as for a wholesomeness greater than that of any other accessible form of spirit, and for a popularity which is the natural result and outcome of its qualities.

As hypocrisy is the homage which vice pays to virtue, so the pains which have been taken to call silent spirit by the name of Whisky, and not only by the name of Whisky, but by the name of Irish or even specially of Dublin Whisky, is a better tribute to the extent of its popularity than all which we could urge on its behalf. For several years past it has been worth the while of certain dealers to incur the expense of conveying millions of gallons of Scotch and English silent spirit to Ireland, and generally either to Dublin or to Belfast, only in order to bring it back again under cover of a Dublin or Belfast permit, so that it might be falsely palmed off upon purchasers as of Dublin or Irish manufacture. In many instances the spirit has been returned on the same day as that on which it was landed in Ireland, and in the same casks; and it gained in selling price, by bearing an Irish permit, more than the cost of the freight both ways across St. George's Channel. Of late years, since silent spirit has been largely made in Ireland, so that the supplies for so-called blending purposes, that is to say, for reducing coarse provincial Whisky by means of silent spirit, have been to a great extent of home manufacture, not indeed Irish Whisky, but truly Irish spirit-the chief aim of importers has been to obtain the Dublin or the Irish permit, by which their foreign rubbish was palmed off upon the purchaser as Irish Whisky too. The unchecked continuance of recent practices would, undoubtedly, in a few years, lead the public to the apparent or supposed discovery that the good qualities of Irish or of Dublin Whisky had no better basis than the fond imaginations of a former generation of men; and the Authors will have fulfilled the task which they have undertaken if they show, as they must unless their demonstration should fail to do justice to the facts of the case, that real Dublin Whisky is still as excellent a commodity as at any former time and that it still possesses all the high qualities for which it was prized and consumed by our forefathers.

The Times newspaper, in commenting upon the adulteration of seeds, in a leading article published on the 4th of December, 1877, points out, with too much truth, that consumers are generally the last to care what they are paying for; but, in the present day, it is only by so caring that they can have any hope of escaping from the great and growing evil of fraudulent adulteration or substitution. It is one of the objects of this book besides explaining what the qualities of Dublin Whisky are, and how they are secured, to point out also in what way the purchaser may guard himself against being, deceived, and may render himself certain of obtaining Whisky when he asks for it and pays for it. In order to afford the public this protection, we must, as a sine quâ non, obtain their own intelligent co-operation; and we have the satisfaction of knowing that the tricks practised in the Whisky trade are so transparent that nobody who has once been told of them need ever again be deceived, if he will only take the trouble to be upon his guard. In this matter, as in so many others, a rogue is only a fool with a circumbendibus; and the traders who, for the sake of a brief time of profit, have been bent upon destroying one of the national industries of Ireland by the substitution of an inferior article for the time-honoured product, are very transparent in their ways. Like the fabled ostrich, they think themselves secure from detection as long as they can conceal the head of their offending; but they forget that this security lasts only so long as no hunter is in pursuit of them. We have made it our deliberate business to expose their devices, and we shall not leave any means untried by which an object in every way so desirable may be attained.

CHAPTER III. - PECULIARITIES OF THE DUBLIN MANUFACTURE: THE WATER SUPPLY.

We have already stated, or have allowed it to be inferred, that the Whisky manufactured in Dublin by the well-tried plan of pot-still distillation, and of maturation by age alone, is superior to any that is made, even upon the same method, at any of the provincial distilleries; and we have explained this by reference to the advantages enjoyed by the Dublin houses in their great command of capital, of experience, and of skill, and also in the vastness of the scale upon which their operations are conducted. Their experience, in each case, is not only that of a single lifetime or generation, but it is tempered by the traditions handed down from generations which have passed away; and we constantly find that such empirical knowledge is in advance of the scientific or theoretical knowledge which is contemporaneous with it, and which often finds its best occupation in explaining the grounds of the truths which experience has already discovered to be true. Especially in the conduct of fermentation does this knowledge, based upon experience, come into constant use and application; and there are certain signs, as slight and indescribable, perhaps, as those which appeal to the proverbial weather wisdom of shepherds, which warn the old hand when it is time for him to intervene.

Signs of equal importance, and, it will be claimed, of even more precision, may be obtained by the application of scientific tests; but the mental perception of the experienced man is instantaneous, while the tests take time, and allow the best moment for action to pass away. Again, the Dublin houses, being practically exempt from the destructive competition downward in respect of price, which involves the spoiling of so many ships for the sake of saving a half-pennyworth of tar, are always in a position to buy the very best grain which is for sale, without allowing any other consideration than that of quality to interfere with them for a moment. The price of materials, and the quantity of product, are with them only secondary considerations ; the first consideration being always and simply to make the best Whisky which it is possible for capital and skill to produce. Besides the powerful operation of these artificial causes, the Dublin manufacture is much indebted to a natural one, namely, to the character of the local water supply. It is well known that many great breweries are placed in a similarly advantageous position; that the water of the famous Southwark well has been largely contributory to the reputation which enabled Dr. Johnson, in his well-known advertisement of the business, to say that it implied a potentiality of wealth beyond the dreams of avarice; that some of the other London brewers are similarly favoured; that the water of Burton-upon Trent forms part, at least, of the secret of the excellence of its ale, and that, to take an illustration from nearer home, the water of Dublin is the source of the stout which has made the name of Guinness a household word wherever there are civilised men who experience the sensation of thirst.

All these various kinds of water have special powers of dissolving vegetable matters and of retaining vegetable aromas; and the water which is so excellent for stout is equally available for extracting the virtues of malt or grain in order to present them to the consumer in the form of Whisky. It is a very curious experiment to bring some Dublin water to London, and to make two infusions of tea, alike in all respects, save that one is made with the imported and the other with the London water. The former will be found to yield at once a more fully flavoured and a more deeply coloured infusion, showing that the Dublin water is a more powerful solvent than that of London. An analysis by Professor Wanklyn has shown that the water of the Canal which is used by us is alkaline to an extent which equals the presence of a pound and a half of carbonate of soda in 1000 gallons. The alkalinity in question is derived, of course, from filtration through the earth; and it is a curious though familiar fact that the natural medication of water by this process of earth filtration cannot be imitated by art. Chemists make the most precise analyses of medicinal mineral waters, and these are then imitated by laboratory processes until no tests could distinguish the original from the imitation-no test, that is, save one, the test which is applied by the human system when the water is taken as a remedy. No artificial substitute or imitation, even although to all appearance the same thing, ever fully equals the effect of the original; and it is the more necessary to lay stress upon this established lesson of experience, lest some maker of bad Whisky should try to improve his results, and to imitate Dublin water by adding to that which he employs a modicum of soda.

We should explain also that the actual alkalinity, although estimated in terms of soda, does not consist entirely of that substance, but also of lime and of magnesia; so that an exact imitation is less than ever practicable In other respects the water is of average drinking purity, and presents no discoverable peculiarities It does not from this follow that it may possess none; for our faith in the growing science of chemistry is not sufficiently profound to induce us to place entire and absolute reliance upon all of its positive, and still less, therefore, upon all of its negative results. Because things are not discovered, it does not follow that they may not be there; and we speak of the special value of Dublin water for Whisky making, from the results of long experience, as a fact about which there can be no question, and which may or may not be adequately explained by the alkalinity which we have mentioned. We contend only for the fact, and for its importance in pointing to Dublin as the natural home of the manufacture; and we leave the explanation, in the grand words of a wise man who lived nearly three centuries ago, to "Time, the Discoverer of the Truth."

CHAPTER IV. - PATENT STILLS AND SILENT SPIRITS.

We have already explained that when a fermented mash is distilled in a pot-still, the product contains not only alcohol and water but also a number of flavouring matters, vegetable oils and essences, yielded by the substances from which the mash was made, and that these flavouring matters serve to differentiate spirit obtained from different sources, and to declare the character of the mash. Not to speak of minor distinctions, spirit distilled from a grape mash is brandy, and has distinctive characters of its own. Spirit distilled from a malt or grain mash is Whisky, and also has distinctive characters. Spirit distilled from a cane sugar mash is rum, and could scarcely be mistaken for anything else. When the raw materials of the distillation are themselves of good quality, we obtain from them good brandy, or good Whisky, or good rum, as the case may be; and these products require only time and maturity to bring them to perfection. If, on the other hand, the raw materials are partially spoilt, or ill-flavoured, or in any way inferior, we still obtain from them brandy, or Whisky, or rum, but the quality of the product is inferior, in a degree determined by the inferiority of the source from which it was obtained. If the product, although inferior, is drinkable and marketable, it will command a certain price as a spirit of second or third-rate quality; but, if it is not drinkable, it must be in some way altered before it can be sold.

For this purpose it is submitted to a process called rectification, which essentially consists in re-distillation, with the addition of certain chemical solvents, chiefly of an alkaline nature, which serve to retain some or all of the objectionable matters in the body of the still, and to prevent them from passing over with the new, or second, or rectified product. Now, there are some original conditions of the spirit in which the taint to be removed is only slight, and in which it can be removed without at the same time removing the peculiar characteristics of the brandy, or Whisky, or rum, as the case may be; or, in other words, there are varieties of brandy and of Whisky and of rum which may be improved by slight rectification without loss of their distinctive characters. Something disagreeable has been taken out of them, and they are still what they were before, not of first-class quality, but better for the process to which they have been subjected, and still marketable. Again, there are certain varieties which are so nasty, or so deeply tainted from the faults of the raw material, that the taint can only be removed by a degree and amount of rectification which removes the distinctive characters also; and then we no longer have rectified brandy, or rectified Whisky, or rectified rum, but only rectified spirit, from which everything distinctive of brandy, or Whisky, or rum, has been taken away in the process which it has undergone.

Rectified spirit is a great solvent of vegetable matters, and also a great preservative of them, and hence it is much used in medicine to make the preparations known as tinctures. It is kept by all dispensing chemists, and may be sold by them in small quantities without a spirit licence. It should consist of nearly equal parts of absolute alcohol and water; and the best way to become acquainted with its qualities is to buy a little from some chemist and to examine it. It is a limpid, colourless, highly inflammable liquid, which quickly dries up or evaporates, and which should leave no smell behind. It has what is described as a penetrating odour, but this is not really an odour, but a stimulation of the lining membrane of the nostrils by the irritating vapour. Alcohol has a great craving or affinity for water; and the rectified spirit, although it has received some water, has not received enough to satisfy this craving, so that it seeks to withdraw more from the moist tissues of the body whenever it comes in contact with them. It is by thus attracting the water of the tissues that it irritates, and that it seems pungent to the nose, and hot to the tongue or throat, when tasted or swallowed. The action of the substances called caustics is, generally speaking, of a similar character; that is to say, they produce smarting, or heat, and ultimately destroy the living tissues, by abstracting their water from them. Besides being the basis of many medicines of which it forms a permanent part, rectified spirit is very useful as a solvent in extracting the active parts of certain medicinal plants, such as morphia and quinine, and its power as a solvent of gums renders it of much value as a basis of varnishes and other preparations.

The high price placed upon it by the excise duty was for many years practically prohibitory of its employment in this country for purposes for which it is essential; and hence certain industries which were largely carried on in France could not be carried on in England, on account of the cost of the necessary spirit. This difficulty has been overcome of late years by the discovery that spirit may be impregnated with an offensive substance called "Methyl," which cannot be removed by rectification, and which is so nauseous that it cannot be drunk, but which does not in the least diminish the solvent qualities. This methylated spirit is allowed to be sold duty free, being wholly unfit for human consumption ; and it has rendered possible the unrestrained employment of spirit in the arts, and has also, therefore, enormously increased the demand.

Nearly fifty years ago, a Mr. Coffy invented a still which may be roughly described as intended to combine, in its action, the two processes of distillation and of rectification-by sending over alcohol and water alone, and by arresting or destroying all the flavouring matters which are derived from the mash, and are sent over in pot-still distillation. For many years this invention remained comparatively little utilised, because the demand for rectified spirit was limited; but, with the increasing demand for various purposes which was incidental to many improvements in industrial processes, it soon became apparent that many sources of starch and sugar, although wholly useless for making spirit which would retain the flavour of the mash, would be perfectly and cheaply available for making spirit intended to be flavourless; and so the patent still became the recipient of a great many matters which had previously been wasted; and it succeeded in making spirit from them all. In its earlier days there were a good many failures, or partial failures; that is to say, the still allowed matters to pass over which it should have retained. This was not a fault of the invention, but was a result of carelessness in using it; and it has been gradually, but not altogether, set aside by experience.

In spite of experience, workmen will sometimes be careless; and some unknown Scotch distillers, who wrote to the Times in February, 1876, complained, simply and piteously, that their patent still products were sometimes very nasty, and fit only for methylation. In other words, their workmen were ignorant or careless, and the spirit, instead of being "silent," told tales of its origin.

As a rule, however, due care and skill being assumed, the patent still sends over what is practically a rectified spirit, having no distinctive qualities, telling no tales to nose or palate of the source from which it was obtained, and hence, in the almost poetic language of the trade, commonly called "Silent" spirit.

The owner of a patent still, therefore, instead of being confined, like a Whisky distiller, to the use of the best materials, which would command a high price for various purposes, is able to make his spirit from anything that comes to hand, and with little reference to any other quality than cheapness. The manufacture of silent spirit is practically based upon the utilisation of waste products.

We have already hinted at some of these waste products, and we are unable even to attempt to enumerate all of them. From time to time, some enterprising distiller finds out some new raw material, and keeps his secret as long as he can. Occasionally, no doubt, more especially in dealing with new material, the patent still tells tales, and produces spirit fit only for methylation; but difficulties hence arising are merely stimulants to manufacturing ingenuity and enterprise.

In no long time after the general employment of the patent still, a spirit perfectly silent, a simple rectified spirit, could be produced at much less than the cost of Whisky; and this was speedily used to adulterate the Whisky of the Dublin houses on its way from the maker to the consumer. Sometimes, no doubt, the products of patent still distillation were not quite without character; but it is manifest that they might bear traces of their origin and yet not be so vilely flavoured as to be necessarily used only for the preparation of methylated spirit. As a rule, the samples were such as would have passed muster with a chemist for rectified spirit; and they would have, properly speaking, no taste, but only the alcoholic penetration and pungency. Such spirit would no more be Whisky than it would be brandy or rum, although it would contain the alcohol which is a necessary ingredient in all these liquids, and would possess the solvent power necessary in order to take up and retain flavours when these were artificially added in the after processes of manufacture. If was a mere basis, a foundation, plastic to the hand to the compounder, and capable of being converted into sham Whisky, or sham brandy, or sham rum, as well as into honest doctors' stuff or into good varnish. As no one could ascertain by any examination of the product what was the material from which it was derived, so it contained nothing which could undergo any spontaneous maturation or development; and being silent spirit, approximately pure alcohol and water on the day when it was manufactured, it remained absolutely without change, save that it would lose strength by evaporation for any period of time. As we have seen already, all pot-still spirit steadily improves by keeping, and improves in quality far more than it deteriorates in strength; so that a Whisky originally twenty-five over proof, and worth, say, four shillings a gallon, if kept for ten years, or until it had fallen by evaporation of spirit barely to proof strength, would have gained very much more in value by its higher quality than it would have lost by its reduction in alcohol.

It is therefore worth while to keep Whisky, but in the case of silent spirit there is no beneficial change to balance or exceed the loss of strength by age; and hence there is not only no inducement to keep such spirit, but every possible inducement to be rid of it as quickly as possible, on the very day of distillation, if circumstances will permit. It is then as well-flavoured as it ever will be, and stronger than it ever will be again. The dealers in sham Whisky, therefore, when they advertise "age" as one of the qualities of their precious compounds, are advancing what they well know to be a statement wholly opposed to the truth, since the prosperity of their business and the lowness of their prices essentially rest upon selling without delay, and upon the activity of what they term "the nimble sixpence." Of course it is possible that there may be, here and there, private customers, or even publicans, who are so little aware of the nature of sham Whisky that they lay it down to improve by time; and, as hope is the mother of credulity, it is even possible that some of these confiding persons may imagine that their hoard has earned interest upon their outlay. In this belief, however, they are totally and lamentably deceived. As we shall have to show hereafter, it is quite possible that sham Whisky may undergo some deterioration, at least in the sense of being even less like the real spirit than it was when it was first made; but it is impossible that under any circumstances it can improve. The consumers, if such there be, who like it and drink it knowingly, may comfort themselves with the knowledge that it is as good when fetched in a pitcher from the neighbouring public-house, as it would be if bottled by themselves, and kept religiously even for generations.

To recapitulate what has already been advanced, we may repeat that silent spirit is distilled from all sorts of materials, in a still which has the property of preventing the peculiar characters of these materials from coming over and asserting themselves; so that the product of a successful distillation is simply rectified spirit, pure alcohol and water, or nearly so, without distinctive flavour or quality, and without capacity for improvement. It is worth, on an average, about two shillings a gallon, and it can be obtained from some foreign countries at a still lower price. There has lately been a Russian silent spirit in the market, at a price of eleven-pence a gallon, the sources of which are not generally known. It is obvious that a spirit distilled from first-class grain or malt, by a process requiring the closest skilled supervision and a very costly plant, can never compete, as regards mere cost, with even the native products of patent still distillation.

CHAPTER V. - THE GROWTH OF SILENT SPIRIT INTO SHAM WHISKY.

In nearly every anatomical museum there lingers a grim story, dating from before the days of methylation, of some former porter or other custodian or servant, whose wont it was to obtain the means of inexpensive inebriation by drinking the spirit out of the preparation jars. In those days, good rectified spirit was used for preparations; and the value of the duty-paid spirit in a large museum, and the cost of replacing the annual loss by evaporation, even if not by drinking, was enormous. At present, nothing but methylated spirit is used for such purposes, and it is not only comparatively cheap, but so nasty that as yet no porter has been suspected of drinking it. Even in the old days, the taste which thus displayed itself was one to be marvelled at, for the taste of rectified spirit is not inviting; and, if it were offered to the public, even under the name of Whisky, in its pure or natural state, it would probably find but few purchasers. Of this, anyone may convince himself by buying a little rectified spirit at a chemist's shop, and by tasting it both in a pure and in a diluted condition. Accordingly, the attempt to sell silent spirit for Whisky was not made all at once, but only by slow degrees.

In the first instance, a dealer would buy from a provincial distillery a thousand gallons or so of a coarse, new, strongly tasted genuine Irish pot-still Whisky, and, at some bonded warehouse, say at Belfast, would mix - we beg pardon, would "blend"- this with another thousand gallons of silent spirit, imported for the purpose; he would then have two thousand gallons of a liquid which he would sell under the name of Whisky. The real Whisky in the mixture would, perhaps, be worth 4s. 6d. per gallon, and the silent spirit would, perhaps, be worth 2s. 6d. The former would be too strongly tasted, the latter would have no taste at all. It is obvious that the effect of mixing the two would be to produce a milder liquid than the genuine Whisky employed, and that the mixture might be passed off as having greater age, or originally better quality, than it really possessed. It must be observed that there would be no real improvement, because the strong flavours of the real Whisky would not have been decomposed or otherwise modified by time, but only disguised by dilution; although it must be conceded that, if these flavours were hurtful, as there would be less of them in a given quantity of the mixture, this would be more wholesome than the young Whisky which was used. Unless with very skilled buyers, however, the general effect would be to make the mixture appear to be Whisky of better quality and greater value even than that of the moiety of real Whisky which it would contain; and so, assuming the moiety of Whisky to be worth £225, and the moiety of silent spirit to be worth £125, the two together might attain a selling value of, say, £500, as a mere result of the mixture. The value would, of course, be a deceptive and not a real value; or, in other words, the mixture would not be worth £500, but would only be capable of being represented to be so to those unacquainted with the way in which it had been produced.

The betrayal of the secret would have destroyed the augmentation of value. The chief evil of this practice was that it threw into circulation, for drinking purposes, a quantity of young Whisky which contained. fusel-oil and other impurities which time would have removed, which was not really fit for consumption, but which was rendered acceptable to consumers by being diluted with silent spirit. The fusel-oil and such like matters have been accused, we do not say whether rightly or wrongly, but, at all events, very often and very decidedly, of being far more injurious to the human organism than the alcohol which suspends or dissolves them; and it is affirmed that young and immature Whisky occasions a peculiarly insubordinate and violent form of drunkenness. The venerable story of the old Scotchman, who palliated a row on a Sunday by explaining that "The Whusky war that bad, that the lads had nae respect for the Sawbath-day," although venerable, is none the less the expression of a belief that still endures, and much of the violence of the intoxication of our large towns has constantly been ascribed to the adulterated and bad quality of the spirit sold at common public-houses. To quote a happy phrase which was lately used by a correspondent of the Times, this violent drunkenness is a result not of alcohol, but of more noxious matters combined with it; it is, strictly speaking, poisoning intoxication, and not inebriation or mere drunkenness.

To return from this digression to the ways and works of the "blenders," we may say briefly that these persons were soon found engaged in the development of their new business; and they tried a vast number of curious and instructive experiments in their endeavour to solve the great problem of how bad and how inexpensive a liquid might be substituted for Whisky, and yet palmed off upon the unsuspecting public. We have before us the records of many "blends," some of them containing silent spirit from a single source, some containing five or six varieties, perhaps added together for the convenience of dealing at once with several job lots, some containing none but provincial Whisky, others containing a small quantity of genuine Dublin Whisky, but none of them open to the charge of extravagance in the use made of the last-named costly ingredient. Fortunately, particulars of all the blends are officially recorded, and those who know how to proceed may obtain a full account of them. We subjoin the particulars in four instances, which will serve to illustrate the sort of thing which is done every day. Only one of them, however, is a mixture of the comparatively innocent kind to which we have as yet referred; and one, to which we shall come in its turn, contains no Whisky at all.

The mixture to which we will first call attention, and which may be described as No. 1, was made in Dublin in December, 1875. It contained :

Spirit, presumably silent, from Haig, Cameron Bridge - 1173.6 Galls.

Spirit, presumably silent, from Watt, Derry - 479.2 Galls

Spirit, presumably silent, from Walker, Limerick - 753.2 Galls

Provincial Whisky, from Daly, Tullamore - 1554.4 Galls.

Provincial Whisky, from Devereux, Wexford - 1958.2 Galls.

Dublin Whisky, John Power and Son - 786.0 Galls.

---------------------

Total: 6704.6 Galls

It will be observed that, in this instance, we have 3512.6 gallons of provincial Whisky, presumably of no great age, since otherwise it would not have borne dilution, and that this was diluted with more than two-thirds of its bulk (2406 gallons) of silent spirit.

In this way the strong taste of the Whisky would be brought down without diminishing its alcoholic strength, and a fictitious appearance of greater age and better quality than it possessed would be conferred upon it. It was probably intended that the result should pass muster as Whisky with purchasers who had some faint notion of the meaning of the word, and of the characters which the genuine article ought to possess; and so, in order to improve the imitation, or to render the resemblance more deceptive, a modicum of real Dublin Whisky, from John Power and Son, and in the proportion of no less than 786 gallons to 5918.6 gallons, or a little more than 13 per cent., was added as a finishing touch to the compound. We shall find hereafter that there would be nothing remarkable or unusual in the occurrence if this "blend" had been put into old casks of John Power and Son, and had been sold as their Whisky; although in the particular instance we have no reason for suspecting that such was the case.

However it was sold, such was its composition; and it is this sort of combination of a great deal of silent spirit with a small quantity of Whisky which dealers describe to their customers and the public as the last result of years of study, and of the highest refinement of skill, and which they represent as being better-Heaven save the mark!-than the genuine Whisky to which it owes the only merit it can possess. It is perfectly plain that the only motive for bringing 1173 gallons of silent spirit from Scotland to Dublin, and the only motive for bringing 1232 gallons from Derry and Limerick to Dublin was that all this might be made to appear to be of Dublin manufacture. It would all be shipped to England under a Dublin permit; and to obtain this permit, in support, or apparent support, of a false pretence, the makers were ready to pay freight and carriage for the whole of the 5918 gallons which they had collected together to receive a character from the 786 gallons of real Dublin Whisky which they were so extravagant as to throw into their witches' cauldron. We confidently appeal to the common sense of the public for an answer to the question whether this class of dealing falls far short of fraud.

Blend No. 2, to which we shall next direct attention, differs from the foregoing in containing no Irish spirit at all, except a minute proportion, probably a chance residue, amounting to 298 gallons in a total of over 8000. It was thus composed :

Spirit, presumably silent, from Menzies and Co., Edinburgh 2989.7 Galls.

Spirit, presumably silent, from Haig, Cameron Bridge 1623.6 Galls.

Spirit, presumably silent, from Harvey, Glasgow 2120.7 Galls.

Spirit, presumably silent, from MacFarlane, Glasgow 1162.5 Galls.

Spirit, presumably silent, from Watt, Derry 298.8 Galls.

----------------------

Total - 8195.3 Galls.

This second blend was made in the same month as the preceding one, and by the same firm of dealers but, before we enter upon the question of the precise significance of its composition, we must say something about the extent and manner in which similar practices are carried on at Belfast, where upwards of 3,000,000 gallons of British spirits were blended in the year 1875, before being sent out for consumption. We subjoin two examples, for which we are able to give the dates at which the several parcels of spirit were warehoused, and thus to show to what extent the question of age enters into these mixtures.

Blend No. 3 was composed almost entirely of presumably silent spirit. It was made in Belfast, on the 29th of September, 1875; and it will be observed that the whole of the spirit employed was imported, that all of it had been imported within six weeks, and all but one small parcel within three weeks :

Blend No.3

| Gallons | From | Warehoused |

| 534.7 | Walker and Co., Limerick | Aug. 16, 1875. |

| 373.0 | Menzies and Co., Edinburgh | Sept. 8, 1875. |

| 149.4 | Stewart and Co., Kirkliston | Sept. 18, 1875. |

| 1122.7 | Harvey and Co., Glasgow | Sept. 18, 1875. |

| 406.3 | Stewart and Co., Paisley | Sept. 24, 1875. |

| 672.6 | Stewart and Co., Kirkliston | Sept. 24, 1875. |

| 1505.4 | Preston and Co., Liverpool | Sept. 24, 1875. |

| 341.5 | Stewart and Co., Kirkliston | Sept. 28, 1875. |

| 5105.6 Total |

Blend No. 4 contains spirit of quite respectable antiquity. For some unintelligible reason, but perhaps on account of slackness of the market, some of it had been in stock five months, and all of it at least four months. Here it is the time and place of mixture being Belfast, June the 9th, 1875

Blend No.4

| Gallons | From | Warehoused |

| 644.1 | Bruce, Comber | Jan. 19, 1875. |

| 129.2 | Bruce, Comber | Feb. 1, 1875. |

| 129.5 | Bruce, Comber | Feb. 1, 1875. |

| 1925.2 | MacFarlane and Co., Glasgow | Feb. 4, 1875. |

| 1296.3 | Walker and Co., Liverpool | Feb. 4, 1875. |

| 1023.5 | Walker and Co., Liverpool | Feb. 4, 1875. |

| 1269.4 | Menzies and Co., Edinburgh | Feb. 3, 1875. |

| 6417.2 Total |

In these three last blends it will be seen we have a total of 19,718.1 gallons, in which only three parcels, of 298.8, of 534.7, and of 902.8 gallons respectively, were Irish at all, and that two of these three parcels were not made at the place of blending, at Dublin or at Belfast, but were sent there in order to receive the advantage, if such it is to be considered, of a Dublin or a Belfast permit. The rest of the 20,000 gallons, using round numbers, was all Scotch or English spirit; and upon all this the dealers had gone to the trouble and expense of taking it to Ireland only to bring it back again. The course of action which we have traced out with regard to this 20,000 gallons we could trace out equally well, did time and space permit, with regard to millions of gallons more, but to do so would be tedious, and would lead to no useful purpose. The four blends given above are those of which we have previously published the particulars in a pamphlet which has been widely circulated, and with such information that every one in the trade may easily see by what firms they were put together; but the accuracy of our account of them has remained absolutely unchallenged, except that, in the former edition of this work, we fell into the error of considering that the 902.8 gallons supplied by Messrs. Bruce, of Comber, near Belfast, and incorporated in blend No. 4, were to be reckoned as Scotch spirit. It will be manifest that this very trivial inaccuracy leaves the case substantially unchanged, and in no way affects the general argument, and it is mainly for this reason that we adduce the same examples again. The object of the whole proceeding was to sell Scotch or English silent spirit under the name of Irish, and, if we mistake not, under the name of old Irish Whisky; and we shall presently see that the fraud which taints the very inception of such a scheme has to assume a still more aggravated form before its aims can be perfectly achieved. Even with a Dublin or Belfast permit, silent spirit in its natural state cannot be sold for Whisky; and, therefore, when there is no Whisky in the compound, an attempt must be made to imitate the taste and appearance of Whisky by other means.

The only preparation to which genuine Whisky is subjected, if preparation it may be called, is that it is generally suffered to mature in sherry casks. For this purpose, these casks are bought up from wine importers, and the Whisky derives from them a certain colour, and perhaps also a certain vinous flavour, which it would not otherwise possess. The fact that sherry casks are so used has become a piece of popular knowledge; and hence consumers expect Dublin Whisky, or, as they now generally call it, Irish Whisky, to have some indication of a sherry flavour; and here, in passing, we should call attention to this question of name - Irish or Dublin - which is one of more importance to the present question than it might at first sight appear. When the Whisky made by our firms gained its great reputation, it was, of course, "Dublin" Whisky; but, as it was almost the only Irish Whisky exported, or known out of the country in which it was produced, it was in those days quite sufficiently described as "Irish" Whisky, the word Irish being used especially to distinguish it from the Scotch sort, which, as we have already shown on the authority of Dr. Johnson, was less highly esteemed. Now, however, since smaller distillers of Whisky have sprung up in the Irish provincial towns, making what is undeniably Irish Whisky; and more especially since patent stills have been erected in Belfast and elsewhere, making what is undeniably Irish silent spirit, and is sold under the name of Irish Whisky, we are anxious to impress upon consumers that the equivalent for the "Irish" Whisky of the last generation is the “Dublin Whisky of to-day; and that they must ask for Dublin Whisky if they wish to secure the legitimate successor of the spirit which originally made the name of "Whisky" so famous.

Returning from this digression to the sherry question, and to the supposed vinous flavour of Irish Whisky, it would, of course, be quite open to the makers of silent spirit to put their product also into sherry casks; and, so far, to confer upon it the desired appearance and flavour. To do this, however, would require that the silent spirit should remain in the sherry casks for a considerable time, during which time it would be losing alcoholic strength, and would be doing nothing to promote the evolutions of that "nimble sixpence" to which we have referred. The ingenuity of blenders when met by this difficulty was not long in discovering what seemed to them a more excellent way. There are certain places in the Mediterranean, Cette, and others, where an enormous business is carried on in manufacturing artificial wines; and in manufacturing, among other like compounds, an imitation of the worst public house sherry.